BACK

The Oceans and the Tower of Babel – “The Oceans and the Interpreters”

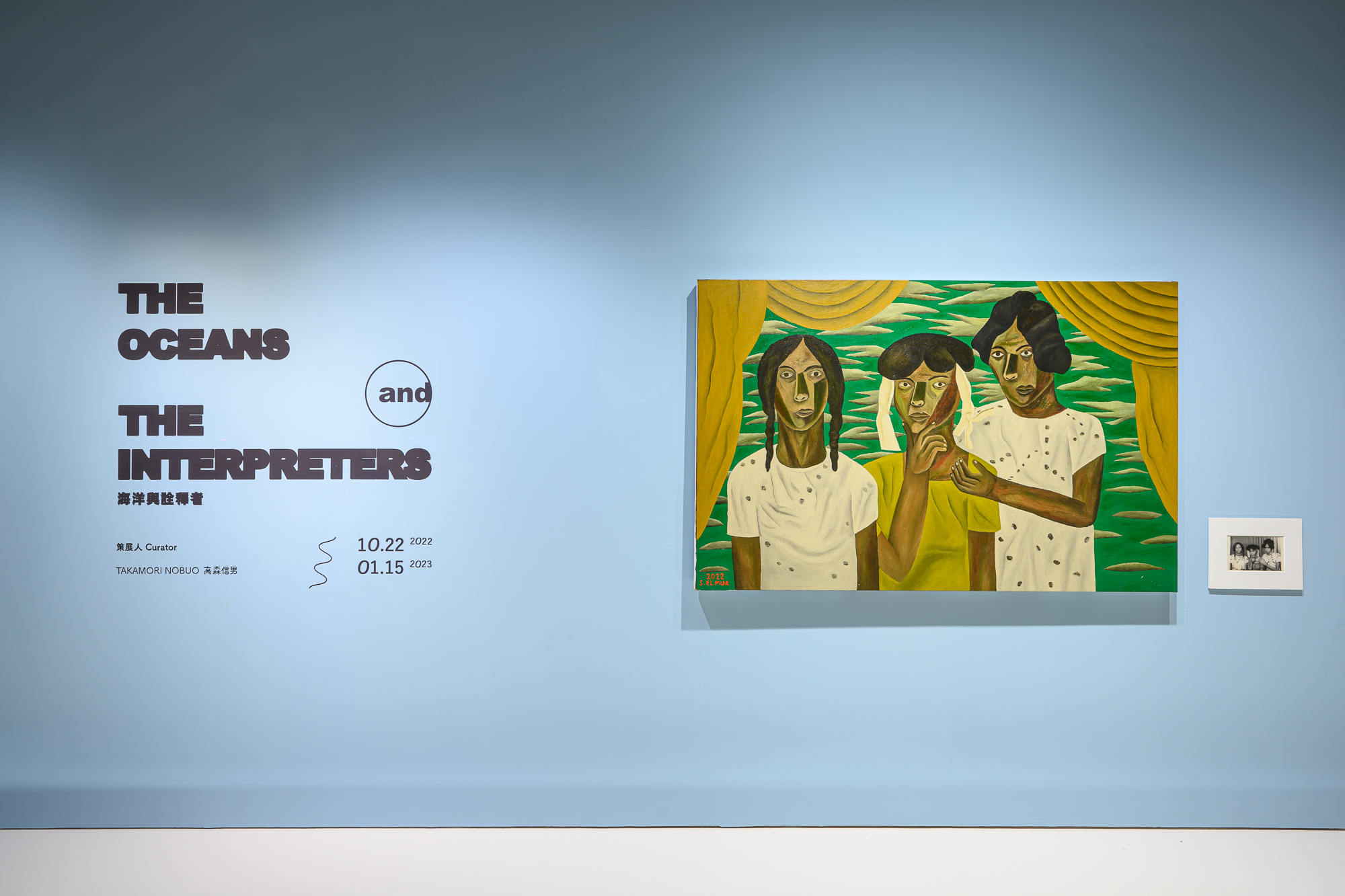

The third season of The Ocean and the Interpreters, curated by Nobuo Takamori, features Salah Elmur’s Green Sky as its main visual, illustrating the unique transience of the exhibition’s content. It appears to be a family portrait, with two women dressed in matching outfits, leaning against a younger brother or sister in the middle, with the mother’s hand resting on her shoulder, slightly tugging her collar. The painting preserves the intimacy of their actions and clothing as presented in the photograph, while the stylized faces give individuality to the characters. The artist changes the background, but they still appear to be in a photography studio, conveying an overall sense of the everyday for these figures, as well as a certain peculiarity when facing the camera lens.

In the juxtaposition of painting and photography, the convergence of these gazes also presents a reversal of stylistic influence. These photographs originate from Studio Kamal, opened by the artist’s grandfather and father in Khartoum. However, what illuminates these photographs—and what first draws us closer to these works—is the modernist style that has been transformed into a localized language. Such a stylistic development stems from the Sudanese Khartoum School of the 1960s, following independence. Its primitivist palette elucidates the controversial manner in which European modernism initially appropriated the legacy of African art, subsequently influencing the evolution of African modern art in the post-independence era. Beyond the realm of visual arts, most post-independence countries also retained the colonial-era borders and languages, thereby encompassing diverse ethnic groups and linguistic communities within their national boundaries. The universality and paradigm of Western culture acquired during colonization naturally became significant cultural and political issues between these Western cultures and indigenous cultures.

Ousmane Sembène, often referred to as the father of African cinema, once said, “Africa is my ‘audience’, while the West and the ‘others (elsewhere)’ are my ‘markets’.” His film Xala (1975) is set in Senegal after independence, where the country has regained control of the Chamber of Commerce from the French. One of the members of the Chamber, El Hadji, marries his third wife on the day of the power handover but discovers on their wedding night that he has lost his virility. Believing it to be a curse from one of his jealous wives, El Hadji seeks the help of a traditional healer when all other avenues fail, only to discover that the one who cursed him is…

Sembène’s depiction of post-independence politics in Senegal is deeply layered with irony, showing how new and old traditions, as well as colonial legacies, continue to influence African countries after independence. El Hadji is corrupt and decadent, living a life centered around European imports, yet in the absence of modern medicine, he turns to traditional healers for help. When speaking to his eldest daughter, he is displeased when she responds to him in Wolof instead of French, yet when he urgently requests to defend himself in Wolof during a voting meeting, the president of the Chamber of Commerce corrects him, insisting, “Even if it’s an insult, you must use the purest form of French tradition.” Another character in the film, the Frenchman Dupont, symbolizes the lingering influence of the old colonizers behind independent nations. Although seemingly stripped of power after transitioning from a prominent role in the Chamber to a mere advisor, he sent chests filled with money to Chamber members, silently observing the drama unfold among them as if watching a play. He follows the president of the Chamber everywhere, hinting at his underlying influence, even when the president tries to introduce a traditional healer to El Hadji, Dupont is discreetly pushed aside, as if to prevent the foreigner from witnessing a spectacle.

Sembène first gained recognition in the French literary circle for his French novels and involvement in the French labor movement. He then went to Moscow in 1962 to study photography before returning to Senegal to make films. His trip to Moscow during the Cold War era in Africa was not an exception; at that time, both the Soviet Union and the United States sought to establish their influence in the newly independent African countries, sometimes instigating coups to install preferred dictators in these countries. This Cold War background also provides historical context for discussing China’s current involvement in Africa. In essence, after the famous Bandung Conference, where China supported Egypt’s reclaiming of the Suez Canal as part of anti-colonial and anti-imperialist movements, and also supported independence movements in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia, China later, during its split with the Soviet Union and during the Cultural Revolution, aided leftist rebel forces in countries like Nigeria, the Congo, and Uganda under Maoist leadership for global revolution. After these smaller revolutions failed, China shifted towards pragmatic politics in the 1970s, cooperating and engaging with existing African governments.

Following the Tiananmen Square incident, when Western countries condemned and boycotted China, a few African countries openly supported China’s actions, while others remained silent. Subsequently, China increased its investments in Africa, leading to closer ties and continued interaction up to the present day.

In the video Waiting (2015) by Ethiopian artist Mulugeta Gebrekidan, the protagonist stands on an empty platform awaiting the Addis Ababa light rail, a project funded by Chinese investment but whose completion experienced significant delays.. This work not only presents the Chinese factor but also continues from an earlier piece, Filling the Gaps (2013), highlighting the significant impact of urban development on culture, history, and identity. In Waiting, the artist, wearing a hat and neat attire while holding a fly-whisk(a traditional symbol of status in Africa), walks towards the incomplete platform. His attire and demeanor contrast with the bustling crowd crossing the level crossing in the background. The plume of smoke emerging from the bottom right corner of the frame also suggests that even this well-dressed traveler on the platform will see his desire for a carefree life evaporate. Interestingly, the platform depicted in the film was eventually completed. However, its operational revenue fell far short of the feasibility studies initially proposed by the Chinese, leaving Ethiopia with massive debt.

Yao Jui-Chung and Hank Cheng’s Chinese Pagoda (Domaine Agro-Industriel Présidentiel de la N’Sele (2020) tells a different story about China. According to Nobuo Takamori’s research, this peculiar Chinese-style building, located near Kinshasa in the Congo, is jokingly referred to by locals as the “Chinese Pagoda” and was likely completed around 1970 or 1971. The appearance of the pagoda, constructed by a team of agricultural advisors from the Republic of China (Taiwan), mimics various landmarks in Taiwan, such as the Chung-Shan Hall in Yangmingshan, Nanhai Academy Science Museum, or the Wujin Temple in Tamsui, all of which are themselves modeled after the Temple of Heaven in Beijing, China. These buildings were nominally headquarters for the Republic of China’s farming teams but were actually used by the Congolese dictator Mobutu Sese Seko as his private palaces. It is still unclear who designed these buildings and what Mobutu’s thoughts were on such designs. He seemed to favor a style known as “Tropical Modernism,” which was the result of the localization of international styles in tropical regions. Another palace of his in Gbadolite, known as the “Jungle Versailles,” is an exaggerated European-style building. Although further verification is needed, I believe that at the time, the “Chinese Pagoda” still carried the task of promoting orthodox Chinese culture for the Republic of China. This was during China’s Cultural Revolution, a period when China not only supported leftist guerrillas in Africa but also extensively distributed Mao’s quotations in the continent. Taking advantage of this, the Republic of China built replicas of the Temple of Heaven and other landmarks internationally to assert itself as the true representative of Chinese culture.

The political ideologies of the Cold War era also continually transcended national borders, forming the themes of works such as Mark Salvatus’ Notes from the New World (2015-20), Naeem Mohaiemen’s United Red Army (2018), and Che Onejoon’s My Utopia (2018). I will discuss Mark Salvatus’ work later in the article. Naeem Mohaiemen’s United Red Army is part of “The Young Man Was” series. The film depicts the historical event of the hijacking of a Japan Airlines plane by the Japanese Red Army on September 28, 1977. The plane was en route to Dhaka, Bangladesh, and the hijackers demanded the release of nine Japanese Red Army prisoners along with a ransom of $6 million.

United Red Army successfully conveys, through the recorded conversations between the hijackers and the control tower, the atmosphere of negotiations, ranging from intimacy to near rupture, and how consensus was reached through dialogue in a third-party language, leading to unintended consequences. On the surface, it appears to be a successful terrorist action where, under the Japanese government’s “exceptional measures,” they successfully obtained ransom and secured the release of their comrades in Japan. However, during the hijacking process, it also sparked another coup at Dhaka Airport, resulting in the deaths of 11 officers and thousands of soldiers. Mohaiemen’s series critically examines the history of these radical leftist movements and argues that they inadvertently fueled the rise of the right-wing. However, in this particular work, the artist, who was an 8-year-old child at the time, was waiting for the TV show The Zoo Gang to resume after an abrupt interruption. Within this frame story, the artist seemed to analogize the hijacking to a heroic tale, thereby retaining a sympathetic understanding on a personal emotional level.

Che Onejoon’s My Utopia brings together these ideologies of transnational migration within individual life experiences. The protagonist of the film, Mónica Macías, the daughter of the dictator Francisco Macías Nguema, was born in Equatorial Guinea. Mónica only learned about her father’s fate later in life. Growing up in North Korea, Korean became her most proficient language, and she came to see North Korea as her homeland. However, due to her skin color, she was never considered Korean and was forced to learn Spanish, the official language of Equatorial Guinea, as the country’s own indigenous languages have been buried in Spain’s colonial history. This experience left Mónica feeling like she didn’t belong anywhere and led her to live in Spain, the United States, and eventually South Korea after graduating.

In the film, Mónica repeatedly asks, “Who am I? Where do I come from? Where should I go?” Her self-questioning and dialogues are sometimes voiced through other female characters, allowing My Utopia to extend her life experiences to other women. These include her Spanish teacher, classmates at the Mangyongdae Revolutionary School in Pyongyang, Anne from East Germany, and Hye-kyung from South Korea, whom she encounters in New York. They all perceive their countries as some kind of utopia, establishing a stereotypical connection between women and national identity. However, their encounters also shape an outlet beyond national ideology, and Korean unexpectedly becomes the common language of these encounters. The artist deliberately includes scenes and camera angles in the film to show that a sense of place is constructed through personal narratives. This allows for the artistic effect of bringing these female characters together as if they are conversing within the same space.

Similar artistic intervention techniques can also be found in Che Onejoon’s other work, Made in Korea (2021), which deals with a similar theme. Since the 1980s, due to labor shortages, many foreign workers have come to Korea to work. Among them, many African workers reside in communities such as Songtan in Dongducheon, Paju, and Pyeongtaek, forming closely-knit communities isolated from Korean culture. They work in factories day and night on rotating shifts, spending their remaining time participating in activities within their own communities, thus having little opportunity to engage with Korean culture. As they are destined to become part of Korean society, Che Onejoon collaborates with them to produce music video works, attempting to use art to break this sense of isolation.

2.

Many works in The Ocean and the Interpreters make extensive use of historical archives. The aforementioned Naeem Mohaiemen’s United Red Army is a paradigmatic example, using audio files to present the context and atmosphere of the events. Other works use methods such as reenactment, interviews, or other interesting approaches to link limited documentary data to various contexts. As contemporary works, they all carefully preserve traces of these connections to prevent the work’s perspective from lapsing into absolutism, as exemplified by Che Onejoon’s My Utopia mentioned earlier.

Carlos Motta’s Corpo Fechado: the Devil’s Work (2018) is a lush and narratively coherent film. The protagonist, Francisco José Pereira, was a slave kidnapped from West Africa to Brazil. Baptized as a Catholic, he developed a religious ritual blending Christianity and African traditions with other slaves. In 1731, when he was sold to Portugal, local religious authorities accused him of practicing witchcraft and “unnatural acts.” He confessed to both charges, admitting to having intercourse with male demons in order to make protective amulets called “bolsas de mandinga.” Eventually expelled from Lisbon, he spent the rest of his life rowing a sailboat. The protagonist narrates his own story, but he does not reach the point of “jouissance” in his account. Instead, through narrative distance, he suggests experiencing two kinds of history—one from the Church’s perspective and the other from the unfortunate intersection of African religion and Catholicism destined to merge. The artist portrays the protagonist as a concrete embodiment of Benjamin’s “angel of history” (in one version of Benjamin’s conception, a fallen angel, a double of the messiah, from his 1933 essay “Agesilaus Santander”), and finally appropriates the iconography of the Virgin Mary holding the crucified Jesus to depict the protagonist as a new messiah.

General Jean Gomis, born in 1933 in Mont-de-Marsan and returning to Senegal with his father in 1948, once said, ‘It must be said, there is no place in the world where black people are highly valued.’ Macodou Ndiaye, born in 1956 in Saigon, only learned his mother’s name from his father’s letter in 1975. Lily Bayoumy, born in Saigon, was found on the battlefield of Dien Bien Phu and discovered she was adopted when her parents passed away in 1988. Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s “Mother, Métis, Memory” (2022, Hong-gah) appears to be inspired by his 2019 work “The Specter of Ancestors Becoming,” focusing on a community of Vietnamese descent in Senegal. During the Vietnam War, some Senegalese soldiers married local women and had children. When France withdrew, some abandoned their families or brought only their children back to Senegal. In this interview film, the artist’s narrative is dispersed, roughly transitioning between different perspectives on the topic. France recruited many colonial soldiers to fight for them in the last century. These soldiers not only fought in World War II but also in various colonial territories, from Vietnam to Algeria, aiding France in suppressing colonial resistance. Thus, these wars involved not only colonizers and the colonized but also conflicts among the colonized themselves. The stories of these Senegalese-Vietnamese communities complicate the relationship between colonizers and the colonized in colonialism. It’s evident that after decolonization, neither Senegal nor Vietnam easily accommodates their life experiences. In Vietnam, these mixed-race individuals face shutters rolling down in front of them on the streets, and upon returning to Senegal, they are mistaken for Chinese. Their mixed identity has a significant impact on family traditions but eventually integrates into Senegalese society. The film appropriately concludes with a song summarizing their struggles in the integration process.

In Au Sow Yee’s “Pirates, the Trembling Ship and their 1001 Nights I: Ron and Row” (2022, Hong-gah), the pirate Abdulla al-Hadj’s life story is only found in a courtroom testimony. He recounts being born in Canterbury, England, and taken to the Middle East at a young age. He later converted to Islam and became a pirate in the northern part of the South China Sea near Borneo, plundering British merchant ships. This court testimony was left behind during his trial after being captured and brought to the East India Company in Penang. The work presents Abdulla’s story as a certain type of narrative: the swashbuckling pirate eventually meets his deserved fate. It mythologizes this genre into a certain archetype, containing both the main developments and underlying inevitable self-conflict or interference. In the film, the British nursery rhyme “Row Row Row Your Boat” serves as a representation of the development of colonial capitalism. In this montage-like historical film, from colonialism to Cold War technology, power extends into both reality and imagination. It encompasses the steadfastness and pleasure of navigation, exploration outward or inward, and science fiction imagination. Like the catchy nursery rhyme, it flows smoothly downstream, representing a blessed journey.

However, this well-planned journey itself contains unexpected internal contradictions. Abdulla al-Hadj’s experiences not only allowed him to cross over the boundaries of identity and culture seamlessly, but his career also practically interfered with the flow of capital. He was a “mysterious man,” and after his trial, he was taken to Bombay “and was never seen again,” disappearing and becoming a ghost of history in the film, yet his name is occasionally invoked. Such invocations become stones that sometimes block the Suez Canal, ultimately leading to the Ever Given blockage incident in 2021. The artist sees in the seemingly omnipotent nursery rhyme of capital and technology an ancient curse continuously experimenting and interfering at unexpected moments. Thus, this journey, blessed as it may seem, becomes entangled with these impediments, resembling a haunting by ghosts, turning the ongoing development into a curse with no end in sight. (Honestly, this work always reminds me of the headscarf kid in “HOKUTO NO KEN -Strawberry flavor” who keeps poking the Holy Emperor Shuu with a knife.)

One of the intriguing exhibition experiences I had was at the Solid Art venue, where I watched a lighting technician using a clamp light to illuminate a rock in a certain film. This was Lin Renda and Yu Zhengzhe’s “Illuminating the Collection” (2022, Solid Art). In the film, the lighting technician appeared to remain still, but in reality, they were simulating the slow movement of sunlight. The rock, named “Sahel rock,” originated from an oil exploration site in Africa, underwent a long sea journey, and eventually became part of the Fireburn Geology Museum’s collection. The rock itself bears witness to geological time, but in the film, it becomes an anchor for experiencing subjective bodily time. The museum behavior of the lighting technician gives a purpose to the involuntary wakefulness of insomnia, yet it’s evidently not an easy task. The trance-like state, the time-consuming nature, and the prolonged gaze reflect various primitive and regressive imaginings on the rock, as well as a pure encounter between human and object. While viewers can understand the vast difference between these two kinds of time, it’s difficult to say whether the connection between the lighting technician and the Sahel rock in the museum is futile.

To a considerable extent, “collection lighting” seems to articulate a certain archival experience clearly. It serves as a preparation, presenting the continuous infusion of external or personal life experiences into collections in a naturalized manner, showcasing the production of knowledge. Another work related to archives is Wang Hongkai and Monu’s “The Mist” (2022, Solid Art). Inside the exhibition hall, there are monthly weather charts of Kenya hanging on the walls, with many books placed on the reading corner table, mainly works by African writers, while songs about the Mau Mau uprising play in the headphones. “The Mist” is inspired by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s description of the Kenyan landscape in “Dreams in a Time of War,” as well as the mystery surrounding how they ultimately lost their land. This work is a preliminary study, and next year there will be a field investigation of the migration path of the Kikuyu tribe in Kenya. Right now, it feels like a long-distance imagining and portrayal of the reality in Kenyan literature from this end of the Taiwan island.

3.

Mark Savatus’s “Notes from a New World” combines an examination of popular music and archives, intertwining popular music with deep-seated colonial legacies. My initial impression of this work was the dissonance of soldiers playing pop music. The video begins with a group of military bands in what seems like a leisure room, led by a conductor performing Rossini’s “William Tell Overture.” Another scene shows the artist’s father’s collection of pop vinyl records from the 1970s. However, this is actually a long-standing military band. It was originally established by the colonial government during the US-Mexico war, called the “Constabulary Band,” led by an African American and composed of Filipinos. They gained fame by playing the same music at the notorious St. Louis World’s Fair. After the war, the Philippine military restructured the band, one of which was renamed the “Philippine Army Band.” They played pop music during the martial law period in the 1970s, contrasting starkly with the vinyl records collected by the artist’s father.

This work explores the ongoing influence of the United States from colonizers to popular music, but what interests me most is the initial dissonance I felt when watching the video. The existence of this military band reflects the complexity of nationalism, which is not merely an imagined community. In roles like the military and police, they are tangible entities. From colonial regimes to post-colonial independent nations, they are needed to uphold various social and cultural boundaries, and when you attempt to cross those boundaries, rifles and batons will remind you of reality – though you might forget after a few years. On the other hand, their forms of expression also seep into the collective imagination of popular culture, like children’s toy police cars, becoming objects of worship in so-called civil societies in places that have experienced martial law. This video also implies other contradictions, such as the performance of Rossini’s “William Tell Overture” by the colonial government to promote local culture, which originally was a story of resistance against tyranny.

Savatus extends the discussion of colonialism from top-down to popular culture, which can serve as a reference point for discussing similar works. “The Currency” (2020, Hong-gah) by Musquiqui Chihying, Elom 20ce, and Gregor Kasper is another piece related to popular music. This work differs in presentation from typical forms, as it requires gallery staff to operate the player in order to listen. It’s a collectively created project published in vinyl record format. The on-site display includes elements of physical music albums, including records with a disc-like appearance and covers, along with long-lost lyrics. This kind of auditory physical display is quite symbolic in this era of streaming music (perhaps especially for rap, a music genre that originated in subcultures but has since been heavily commercialized). On one hand, vinyl records offer the highest quality audio storage; on the other, it seems that only in art exhibitions can music compositions intended to convey ideas receive individual and focused attention.

The experience of listening to physical music is combined with the experience of viewing exhibitions, allowing music content to freely connect various issues. Togolese rapper Elom 20ce narrates from the perspective of a banknote in a briefcase, recounting how villagers in Kpagalam resist the violence of their own country’s military and police forces who protect Chinese mining rights, linking this to the issue of ECO (the Economic Community of West African States) proposing a new currency to replace the CFA Franc, which has been in use since colonial times. Although the plan to adopt this currency removes the requirement for countries using the CFA Franc to keep half of their reserves in the French central bank, it still maintains a fixed exchange rate with the Euro, leading to criticism that it merely renames the colonial-era currency. Musquiqui Chihying’s work uses Alipay as an example, highlighting how China’s economic power is not only used for foreign aid in Africa, as mentioned in previous works, but also for domestic social control through electronic payments. The songs by German artist Gregor Kasper remind us that behind the clean, virtual world created by semiconductor manufacturing and other electronic products lies a reality of labor-intensive, harsh working conditions.

Hoo Fan Chon’s “How to Dance Like a Mudskipper” (2022, Solid Art) places the exploration of objects into the political context of nation-building and cleverly applies it to exercise routines. Mudskippers are one of the recurring themes the artist is concerned with. In his solo exhibition “Biro Kaji Visual George Town” (Narrow Marrow café, 2019.12.14-2020.1.7), he altered the coat of arms of the Penang City Hall because he wanted to localize this emblem inherited from the British colonial period. One of the pairs of dolphins in the emblem was replaced with a mudskipper, as mudskippers are not only commonly seen in Penang but were also once a Malay delicacy. Folklore related to them even became a movie in 1959 called “The Devouring Rock.” Later, in February 2021, the artist proposed an idea titled “Mud-chihoko on Komtar: A Diplomatic Gift Proposal from Nagoya City Hall to George Town, Penang” at the joint exhibition “Nagoya × Penang Simultaneous Exhibition: Nagoya Cultural Center (Nagoya Headquarters)” (Minatomachi POTLUCK BUILDING 3F: Exhibition Space). The proposal suggested replicating the traditional Japanese shachihoko, with Nagano City gifting a pair of mudskipper shachihoko to be installed on the Komtar, Penang’s tallest building.

The artist clearly doesn’t miss any opportunity to promote mudskippers. In “How to Dance Like a Mudskipper,” to introduce mudskippers to the audience in Taiwan, the artist specifically chose tatami floor mats, with potted Ficus microcarpa trees (native to African tropical rainforests, fitting the exhibition theme) placed at the corners. The dancers first introduced the decomposed movements inspired by mudskippers and then revisited the mudskipper movie. Besides the dance, perhaps the most amusing scene in this video is when the dancer steps into the mangrove mud pit and gets ready to teach everyone to dance, with many mudskippers seen scurrying away at his feet. In this work, the artist overlays the image of a healthy national citizen in the construction of national identity with healthy habits from popular lifestyle – these two are not always distinguishable. For instance, Taiwan’s indigenous dance is derived from the military’s promotion during the martial law period. At the same time, he naturally highlights the process of normalization in both the construction of national identity and internet exercise videos from a newly created dance.

Posak Jodian’s “Misafafahyan Metamorphosis” (2022, Solid Art) tells the story of Hao Hao, an indigenous transgender performer, through the medium of song and dance. Hao Hao initially learned hairstyling in his hometown but couldn’t make ends meet. Later, he saw an audition for singing stars and went to Taipei to participate. He performed at the First Hotel on Zhonghua Road and also traveled to Japan, Thailand, and other places for performances. Hao Hao’s performing career went through ups and downs in karaoke bars, Western restaurants, and beef markets, indicating that transgender performers were not taboo in the past public show culture, but their history tends to be ignored and even eliminated with the trend. The standout aspect of this work lies in its use of space. When the protagonist makes his dramatic entrance, he transforms into the form of a backing track. Beyond that space is the protagonist’s family living room, where he washes people’s hair and gathers with family and friends for casual conversations.

Therefore, Hao Hao’s performance evolved from initially eccentric to later revealing warm and intimate qualities. The exhibition features three special works, all of which use concise and interesting creative methods to explore broadly influential topics. Tirzo Martha’s locally produced installation piece, “Emotional Memory” (2022, Solid Art), incorporates materials such as polystyrene hollow bricks, reinforced iron sheets and wire mesh on the wall, hanging used tires, wine crates at the base of the wall, broken wine bottles on the wall for theft prevention, and hanging LED light tubes. The words on the polystyrene hollow brick wall, “AWA AKI,” might be in Papiamento, meaning “water is here.” The artist had a piece with the same name in 2018, which was also constructed using gray bricks, with wire mesh for theft prevention. Using these materials, Martha creates various structures that are roughly able to provide shelter from wind and rain but are not long-lasting or reliable. At the same time, he plays with the subtle tension brought about by the instability of the structures.

The artwork itself embodies the artist’s personal and refined aesthetic vocabulary. When these vocabularies are used to present the commonalities between Curacao and Taiwan Island in architecture, it is also an exploration of the contrasting social conditions between the two places. In the case of Taiwan Island, the creation of these structures is not necessarily related to insufficient financial capability; in reality, they are often more robust than imagined. With various local reinforcements and additions, they can stand for decades. The reasons for their disappearance are often due to factors such as illegal activities, renovations, or urban renewal. However, this impression may also be a survivor bias, as the actual risks to buildings and public safety still exist. Therefore, the precarious balance of tension in “Emotional Memory” represents more like a kind of habitual living with risks as part of everyday life.

Chang En Man’s “Snail Paradise Trilogy: Setting Snail or Final Chapter” (2021, Hong-gah) frames the issue of human origins through food. The protagonist in the film, while tending crops and livestock, sings about the origins of African giant snails, as well as ingredients like “airplane vegetables” and Taiwan fig trees in the melodies of the Paiwan tribe. This work has a simple narrative structure yet manages to raise many important questions. Its scenes suggest the inseparability of human origins and basic subsistence methods. Therefore, when the protagonist suggests following the snails to find the origins of humanity, his approach is to frame this question through the relationship between humans and food. Using food to trace the footsteps of humanity is not easy because humans, as omnivores, don’t have fixed types of food. They not only eat what’s available but also creatively establish customs and hierarchies. These customs maintain the ancient relationship between host and guest at the dinner table, which leads to various changes in culinary cultures. The motive of economic gain brought by colonialism has accelerated species exchange between different regions and alienated the relationship between humans and food.

This narrative framework itself is a form of subjectivity. When the male protagonist finally asks, “And us? Who are we? Where do we come from?” he is retelling Gauguin’s questions from the perspective of an indigenous character. On one hand, this summons the context of primitivism, but at the same time, it expands upon it using the narrator’s authority, extending it into contemporary circumstances. This treatment brings the contemporaneity back into various settings of the film.

Stefanos Tsivopoulos’ “Land” (2006, Solid Art) is the last work discussed in this article. What interests me about this piece is its content and the related interpretations. In the film, three men from different places are on a deserted island, raising numerous questions about the naming, ownership, governance, and borders of the land. These questions easily reveal how artificial political boundaries are imposed on the land, shaping culture and identity. The complexities of these questions are also related to the formal elements of the work. For example, the identities of these three male characters vary across different exhibitions—they are sometimes referred to as survivors of a shipwreck, sometimes as refugees, yet their appearances do not seem to fit these roles. In the film, their identities are as unsettled as the island itself, and they cannot communicate with each other, so their questions cannot be discussed among them—in other words, the island resembles a small Babel. While the identities of these individuals seem open to various marginal roles, the island itself is discussed less. In fact, in the absence of communication, their inquiries are framed in contrast to this island, which is presented with a certain “primitive” color and established reality. How do these people eat? How do they survive here? Sometimes it’s described as an “uninhabitable” island, but is it really? In several scenes in the film, there are distant coastal mountains and nearby fishing boats, so it doesn’t seem like an isolated island.

So what are these neatly dressed backpackers doing here? They seem more interested in being outside of various exchanges on this small island—capital, food, voodoo religion, mixed-race, angels of history, domination, resistance, and so on—all happening within these flows. This kind of exchange used to be a doctrine of naturalistic international law, a European freedom, under which Europeans could freely navigate, travel, and interpret the New World they discovered—when they encountered resistance, occupation and conquest became a just war. All the stories start from here. The island then serves as a laboratory providing observability and a comparative basis, and such a comparative basis also has universality.

After all, what patch of land in the world isn’t an island?

Author|Chen Yu-Jen